- Home

- About UsFTMSGlobal

- Courses in MalaysiaAll Programmes

- Professional Courses: ACCA, CAT, CFA Professional Accounting and Finance

- Professional Accountancy Pathway

- Foundations in Accountancy (FiA) Suite

- Preparatory Course for Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA)

- Oxford Brookes University: BSc (Hons) Applied Accounting (ACCA)

- Preparatory Course for Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA)

- Preparatory Course for Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA)

- MBA ProgrammeAwarded by Anglia Ruskin University

- EnglishFor General, Academic, Business, Finance Studies & IELTS

- Professional Courses: ACCA, CAT, CFA Professional Accounting and Finance

FTMSGlobal Blogs

The Risk Conversation at Board Level

By Professor Andrew Chambers

Andrew Chambers is Academic Director of FTMSGlobal. He chairs FEE’s Corporate Governance and Company Law Working Party. FEE (www.fee.be) is Fédération des Experts-comptables Européens – (Federation of European Accountants). Professionally qualified accountants frequently chair and are members of audit committees of boards and attend audit committee meetings in their capacities as external auditors, chief financial officers, internal auditors, compliance officers and risk managers. The views below are those of Professor Chambers based on his remarks at an ecoDa/FERMA/AIG conference in Brussels.

Abstract:

Risk management is about systematically identifying events and situations that may threaten the entity and positioning the entity to be able to exploit potential opportunities that may arise in the future.

Much has been written on approaches to risk management but much less on how the oversight of risk should be dealt with at the level of the board of directors. A common failure is that the board accepts management’s assessment of risks with too little robust challenge. Another is that oversight of risk is handled almost exclusively at board committee level without in-depth discussion and challenge by the board itself. Handling the interface between the board risk and audit committees is another issue.

The board itself is the biggest risk of the entity, and chief risk officers should have the status to be able to indicate to boards the ways in which this risk is being insufficiently mitigated. The board in particular must engage in the consideration of strategic risk.

Key words:

Corporate risk

Board risk committees

Risk management

Three lines of defence

There are many definitions of ‘risk’, some impenetrable; and risk management is bedevilled by technical terms that serve to exclude many directors and others from meaningful conversations about risk management.

Risk can be defined as:

‘the uncertainty of an event or situation occurring that may impact the organisation.’

This definition captures the reality that risks are not just possible events but may also be found in situations such as non-compliance to legal requirements of government agencies or company policies as well low staff morale due to inability to cope with pressures and demands of the job.

The definition also implies that the board’s consideration of risk should embrace those events or situations that may have positive impacts, not just those that threaten negative outcomes. We might describe these respectively as ‘upside’ and ‘downside’ risks.

Upside risks

With respect to these upside risks, boards should consider whether their risk conversation addresses the likelihood of events or situations arising in the future which could present opportunities for the entity. For each of these significant upside risks the board’s conversation should consider whether or not sufficient measures are in place, or should be taken, to enable the entity to exploit that opportunity, should it occur and should the entity at that time decide to take the opportunity, notwithstanding that it may not have been within the entity’s business plan.

An example was the manufacturer of portable buildings that was unable to exploit the opportunity for quick supply of large quantities of robust, temporary accommodation in the wake of a tsunami. They had not planned to do so and they were unable to adapt rapidly in order to do so. This also can be expressed as a downside risk as competitors moved in and the manufacturer lost global market share from which it is now valiantly endeavouring to recover. The more natural way for the board to handle this and other similar issues is to consider them as potential opportunities that may be foregone rather than as threats that may materialise. Risk management approaches can be applied readily to both upside and downside risks.

Board assurance

Boards are, or should be, burdened with doubt as to whether they are in possession of the assurance they need that their policies are being implemented by management and that the board is fully cognisant of the significant banana skins round the corner, whether or not they are known to management. An open dialogue between the executive and the board is an essential contribution to this assurance that the board needs. Too often top executive teams control the flow of information through to the board to the extent that the board may be kept in the dark about important issues and risks. It is particularly important that the second and third lines of defence (see below) have the authority to communicate independently of the first line of defence to the board’s audit committee, risk committee and to the board itself. Attendance by chief risk officers (CROs) and chief audit executives (CAEs) at board committee and board meetings, together with direct reports from them, should be the order of the day. There is too frequently a tendency for board committees to relegate the reports of the CRO and CAE, as well as of others belonging to the second and third lines of defence, to towards the last item of their agendas, betraying a lack of commitment and interest in what these parties have to communicate.

Increasingly boards are commissioning external reports to give them added assurance, but too often these are commissioned only after disasters have struck. Board committees and their chairs, as well as the board itself, need to ensure that this assurance dialogue occurs proactively.

Lines of Defence

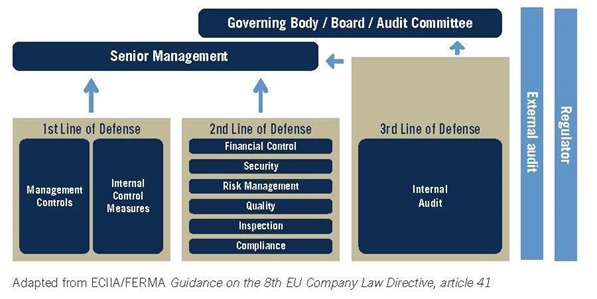

The three lines of defence framework has attracted considerable criticism recently, notably by the UK Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (Chambers (2013 & 2014); HLHC, (2013)). The model is best illustrated in the FERMA/IIA diagram (see Figure 1 below) and has been espoused by others since 2008 (Booz (2008); Sword (2009); Hughes (2011); Basel (2012); Anderson & Daugherty (2012); IIA (2013)). The essence of the criticism of it has been (a) the lack of clear blue water between each of the three lines, (b) the false sense of assurance that the model has been giving to boards, to top executives and to outsiders, and (c) the lack of independent reporting by the second and third lines of defence to boards and to board committees.

Figure 1

The Three Lines of Defense Model (IIA, 2013):

Copyright © by The Institute of Internal Auditors, Inc. All rights reserved

Engaging the board on risk

The risk conversation at board level is often inadequate for many reasons we touch on in this text. It is not easy for the CRO to remedy this – even when the CRO enjoys a direct entrée to the board’s audit and risk committees, and to the board itself. The difficulty is for the CRO to find opportunities to express, albeit tactfully, what needs to be said. The need to do so can be acute as the board, being the most important part of the entity, is the biggest risk of all if it is not functioning effectively, and any failure of the board to focus effectively on risk represents an acutely risky situation. Assessing the quality of the board’s risk conversation should be within scope for the CRO. This has implications for the desirable seniority of the CRO.

The chair of the board is responsible for the effectiveness of the board and for the effectiveness of each member of the board. At board committee level the same applies to board committee chairs. They must bring individual directors ‘up to speed’ on risk management if they are behind the curve or neglectful. It may be a matter of exhortation or a matter of training. It will need a good example by the chair of the board and the chairs of the board’s committees. Prioritisation of the risk conversation at board and board committee meetings is part of the answer to this problem.

A common deficiency in practice is that members of a board risk committee may be mere ciphers, leaning too heavily on the chair of that committee to prepare thoroughly for risk committee meetings and to be active during and between the committee meetings, and leaning too heavily upon whatever the executive reports about risk to these meetings. A related issue is that, where boards are small, each independent director may belong to most or all board committees so that the risk conversation tends to be only a token conversation as each director considers the matter to have been covered already in other fora that they attend. That way, the potential for a separate, distinctive challenge and scrutiny by each committee may be lost. So each committee may fail to take a fresh, objective view of risk, and neither may the board. A further related challenge is the propensity for non-executive directors to lobby for as many meetings (of the board and its committees) to take place on a single day – which encourages tokenism as fatigue sets in.

Committee reporting to the board

Board committees are sub-committees of the board – mechanisms to facilitate the board to discharge the board’s responsibilities well. So it is important to devise effective means of reporting through to the board from the risk committee and the audit committee. It is inadequate for the means of reporting to be via the minutes of these committees which become agenda papers of the board. Too often risk committee and audit committee minutes are ‘B’ items in the board agenda pack – that is ‘for information’ but not ‘for discussion’. The problem will be more acute, because of the time lapse, if the minutes of these board committees only reach the board when a second meeting of the committee has taken place to ratify the draft minutes of the previous meeting. Board committees must report promptly to the board. The business of board committees, not least of the risk and audit committees, is so important that it must be discussed promptly at the board. The best way to do this is for the chair of the board committee to prepare a special report for the next meeting of the board, to present that report in writing as a board agenda paper and orally at the board meeting; and for a full discussion of it then to take place at the board. If this occurs, then it is reasonable for the minutes of these committee meetings to later become ‘B’ items (as defined above) in the board’s agenda pack.

The chief risk officer should be in attendance at board risk committee meetings and when risk is discussed at the board.

Boards need to know whether they have effective internal control, effective risk management, effective financial reporting, effective internal audit and effective risk management functions. They depend in large part on their board committees to give them this assurance. In addition to regular reports to the board, it is likely to be best practice for the board’s risk and audit committees each to provide the board with an annual report that clearly expresses the committee’s opinion and conclusions on these matters. It is one thing for board committees to discuss these matters, but a greater challenge for them to be obliged to draw conclusions from their discussion. Putting it bluntly, what is the risk committee’s overall opinion of the effectiveness of the enterprise’s’ risk management?

Executive risk committees

The CRO should also have the right to attend risk committees at the executive level, as well as to attend Executive Committee meetings.

The need for a risk committee of the board is not satisfied by the existence of one or more risk committees at executive level, even when these executive risk committees report through to the board. Many companies have several executive risk committees – such as the credit risk committee. As with the audit committee, best practice is that the risk committee of the board comprises exclusively independent non-executive directors. It is a mechanism whereby the board, and in particular the board’s independent directors, can satisfy themselves reasonably independently that risk is being identified and managed appropriately. In the UK, the Walker Report (2009) on the governance of banks and other financial institutions allowed that the finance director would belong to the board’s risk committee, but that the members would otherwise be non-executive directors. But the UK Corporate Governance Code (2014) is clear that all the board’s risk committee members should be independent directors. Of course, as with audit committees, appropriate executives will be in attendance for most agenda items, though not as members of the committee.

Sharing responsibilities between risk and audit committees

Now that boards are establishing risk committees of the board, there is a risk that important discussions may ‘fall between the cracks’ and fail to be addressed by either committee, or that there will be excessive overlap between the agendas of the two committees. These risks can be alleviated by having some, but limited, cross-membership between the two committees and perhaps by having occasional joint meetings of the two committees. The responsibilities of audit committees have burgeoned and are continuing to grow, so it is opportune that oversight of risk is being subsumed by board risk committees. Nevertheless there are many facets of risk management which audit committees will continue to address on behalf of the board, especially those that relate to the reliability of financial reporting, the quality of external audit and the effectiveness of the compliance and internal audit functions as well as of other functions within the ‘second line of defence’. It is particularly in the consideration of the effectiveness of the compliance and internal audit functions as well as of other functions within the ‘second line of defence’ that there may be overlap between the two committees – even leading to turf wars as the committees tread on each others’ toes and give conflicting guidance to those who lead the functions within the second and third lines of defence.

The transfer of responsibilities from the audit committee to the board’s risk committee means that the latter assumes responsibility for (a) assessing the quality of the risk management process, (b) reviewing the main, specific risks that the process has identified, (c) satisfying the committee (and thence the board) that these are indeed the key risks to the entity and (d) that they are being managed effectively. Effective internal control is an important way in which risks are managed, and so the risk committee of the board will not be able to avoid considering the effectiveness of internal control although internal financial and accounting control will fall largely within the remit of the audit committee whilst operational control will be largely within the remit of the risk committee.

Where control tends to be weakest is at the interfaces between processes, including the interfaces between operational processes and accounting processes. These points of interface risk not being attended to by separate risk and audit committees.

Risk ownership, sponsoring and shadowing

It is good practice to assign ownership of each risk to a specified executive who may or may not be a member of the board. The risk conversation at the board will be informed by attendance and reporting of executives with ownership responsibilities for key risks. Additionally, some companies assign a ‘risk sponsor’ for higher level oversight of each key risk. Again, the risk sponsor will not necessarily be an executive who sits on the board, but should be so for the most critical risks. Some boards operate a system of ‘shadowing’ whereby an independent director shadows a senior executive. Where this applies the shadow should spend time to master the key risks in that executive’s portfolio of risks.

Strategic risk

In business planning and execution, a common fallacy is to assume that current trends will continue into the future unabated when in reality there is little uncertainty that they will not, and that the future itself is uncertain. Chuck Prince, CEO of Citibank, in July 2007 a month before he lost his job, memorably said:

‘When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will get complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance.’

So, a key element of strategic risk analysis must be to explore the implications of possible future dislocation.

We have already suggested that the board itself is the principal risk of the entity if it is not functioning well, and so it must be one of the risks that is within the board’s risk conversation. Emerging requirements for the board to evaluate its own performance, and with periodic external facilitation of this evaluation, is a means of managing this risk. So the results of the board evaluation must be shared with and discussed at the board – not merely shunted off to a committee of the board or to the board’s chair.

When the executive deviates from the policies of the board it may be because of inherent inconsistencies between different board policies. Boards must consider the risks associated with the interfaces between their policies – especially when one policy rests uneasily with another. For instance, in an oil company the board’s pressure to maximise shareholder return was at odds with the board’s policy to be a safe and ‘green’ oil company. Another example is illustrated by Applegarth, the deposed CEO of the failed UK Northern Rock bank, who is on record as stating that had he gone to the board to commend a more conservative lending strategy , the board would have demurred as it would have reduced shareholder return, at least in the short term.

We have also already suggested that boards must attend to ‘upside’ as well as ‘downside’ risks. We add to this that boards should be aware that risks are like London buses, tending to come all at the same time or in quick succession. Boards should factor this into the board’s assessment of risk: for each significant risk they should consider the possible impact and appropriate mitigation strategies if the risk materialises at the same time as another risk occurs, or shortly before or after. When companies fail or nearly fail it is usually because they have been beset by more than one risk simultaneously or in close order. Too many boards are content with risks being considered serially rather than in parallel, as this is much easier to do.

Important features of the board’s risk conversation should be to explore how the entity is ensuring that risk assessment and management are …

• Top-down (whether and how the board’s and top management’s concerns about risk are communicated downwards to inform risk assessments done at lower levels of the entity);

• Bottom-up (whether and how lower level insights about risk are communicated upwards so that they may potentially inform the top-level risk assessments);

• Enterprise-wide (rather than limited to ‘silos’).

Agreeing the entity’s risk appetite can be an invaluable discussion at board level, though we must concede that risk appetites may appropriately vary for different projects and in different parts of the entity. It is too risky and generally unnecessary to ‘bet the whole farm’ on a particular strategy.

Donald Rumsfeld said:

‘There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don't know we don't know.’

Risk managers might add:

‘And there are things we [as risk managers] know that we don't want to know.’

‘Known unknowns’ and ‘unknown unknowns’ can be approached by scenario risk management: we may not be able to anticipate all the trigger(s) but we can identify possible consequences without knowing what might have been the trigger(s). By way of example, the consequence that we are unable to use our head office for an extended period of time might have been triggered by any number of events.

Non-executive directors on boards often lack the confidence to be an effective challenge of strategy. They may ask a few intelligent questions but then back off from denying approval to the executive of their strategic proposals, reasoning that the top executive team understand the business and the market much better than they do, and have worked hard to develop strategic proposals. To mitigate this risk, it is helpful that at all stages in the formulation of a new strategy, the board discusses the issues and the emerging draft proposals. The discussion should start even before the executive get down to work on formulating a proposed new strategy. At all stages the likely risks should be identified and assessed.

Conclusion

It has been said that profit is the reward for taking risk. In not-for-profit entities better performance may be said to be a reward for taking risk. But this catch phrase is disingenuous. The board risk conversation should lead to a better understanding of risk and better risk counter-measures. The result should be that the entity is better able to conduct itself in ways that lead to greater profit and better performance, without being exposed to unacceptable levels of risk.

There is always a risk that we may be caught out by events and situations that we have failed to identify and manage. But an embedded approach to risk management, including meaningful risk conversations at board level, makes this less likely. Over time, as we refine our approaches to risk management, there should be fewer potential banana skins round the corner for our organisations to slip over.

If all organisations were approaching risk management with similar degrees of sophistication, it would be a zero sum game. The fact that they are not doing so gives a competitive advantage to those that take it seriously.

It has been said of audit committees that ‘cars have brakes so that they can go faster’. The oxymoron is also true for risk committees.

The approach to and content of the board’s risk management conversation is largely at the discretion of boards across Europe. It will be worthwhile for each board to set aside quality time to formulate their approach to their risk oversight, before engaging in the conversation.

References

Anderson, U., and B. Daugherty. 2012. The Third Line of Defense: Internal Audit’s Role in the Governance Process. Internal Auditing, Boston, US, Warren Gorham Lamont, July/August, pp. 38-41.

Basel (2012) Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, The Internal Audit Function in Banks, Bank of International Settlements, ISBN 92-9131-140-5 (print), ISBN 92-9197-140-5 (online), June. [http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs223.pdf, accessed 14th July 2013].

Booz (2008) Teschner, C, Golder, P. & Liebert, T., Bringing Back Best Practices in Risk Management: Banks’ Three Lines Of Defense, Booz & Company, [http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/media/file/Bringing-Back-Best-Practices-in-Risk-Management.pdf, accessed 5th August 2013].

Chambers, A.D. (2013) Maginot Line, Potemkin village, Goodhart’s Law? The third Line of Defense: Second Thoughts (Part I), Internal Auditing 28 (6), Thomson Reuters, ISSN 0897-0378, (November/December), pp. 15–24.

Chambers, A.D. (2014) Maginot line, Potemkin village, Goodhart’s law? Third Line of Defense – Second Thoughts Part 2, Internal Auditing, 29 (1), Thomson Reuters, ISSN 0897-0378, (January/February), pp. 10 - 16.

UK Corporate Governance Code (September 2014) https://www.frc.org.uk/Our-Work/Codes-Standards/Corporate-governance/UK-Corporate-Governance-Code.aspx .

HLHC (2013) House of Lords and House of Commons, Changing Banking for Good, Report of the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards, Volume I: Summary, and Conclusions and Recommendations, HL Paper 27-I, HC 175-I, 12th June. [http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/joint-select/professional-standards-in-the-banking-industry/news/changing-banking-for-good-report/, accessed 14th July 2013]; Volume II: Chapters 1 to 11 and Annexes, together with formal minutes, HL Paper 27-II, HC 175-II, 12th June, [http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/joint-select/professional-standards-in-the-banking-industry/news/changing-banking-for-good-report/, accessed 14th July 2013]. See specifically HL Paper 27-II, HC 175, p10 and HC 175-II, § 133, p. 44.

IIA (2013) The Institute of Internal Auditors Inc., The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control, Position Paper, January. Available athttps://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/Public%20Documents/PP%20The%20Three%20Lines%20of%20Defense%20in%20Effective%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Control.pdf, accessed 20th July 2013].

Sword, C.C.H., The three lines of defence. Available at http://www.risk.net/operational-risk-and-regulation/advertisement/1530626/the-lines-defence, accessed 14th July, 2015):

“In this model, the first line consists of your business’ frontline staff. They are charged with understanding their roles and responsibilities and carrying them out correctly and completely. The second line is created by the oversight function(s) made up of compliance and risk management. These functions set and police policies, define work practices and oversee the business frontlines with regard to risk and compliance. The third and final line of defence is that of auditors and directors. Both internal and external auditors regularly review both the business frontlines and the oversight functions to ensure that they are carrying out their tasks to the required level of competency. Directors receive reports from audit, oversight and the business, and will act on any items of concern from any party; they will also ensure that the three lines of defence are operating effectively and according to best practice.”

Walker, D. (2009) A review of corporate governance in UK banks and other financial industry entities, final report, November, accessed 30th April 2015], see §6.15, pp. 95-6.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

About the author

Qualifications

BA (Hons) University of Durham, UK

PhD London South Bank University

Memberships

European Engineer (Eur Ing)

Chartered Engineer (UK)

Fellow of The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England & Wales

Fellow of the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, UK

Fellow of The Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors, UK

Fellow of The British Computer Society

Chartered Information Technology Professional, UK

Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, UK

Andrew is author of Chambers Corporate Governance Handbook (6th ed., May 2014, Bloomsbury, ISBN 978 1 78043 482 7, 1,100 pages), The Operational Auditing Handbook - Auditing Business & I.T. Processes (2nd ed., Wiley, April 2010, ISBN 0470744766, 884pps) , Tolley’s Internal Auditor’s Handbook (2nd ed., 2009, ISBN 9781405735674, 750 pps), and seventeen other books on these subjects plus translations. He was twice mentioned in House of Lords’ debates as an authority on corporate governance and by The Times as ‘a worldwide authority on corporate governance’. He was Dean of the leading Cass Business School where he is professor emeritus. Appointed in 2010 as the Specialist Advisor to the House of Lords’ Economic Affairs Select Committee’s Inquiry into Auditors: market concentration and their role that led to the current audit market reforms. Andrew was one of a seven member UK committee that in 2013 published enhanced ‘Internal Audit Guidance for Financial Services’. Since 2008 he has been a member and now chair of Fédération des Experts Comptables Européen’s (FEE’s) Corporate Governance and Company Law Committee: FEE is the pan-European association of three dozen professional accounting bodies.

- You are here:

-

Home

-

Blog

-

Professor Andrew Chambers

- The Risk Conversation at Board Level

Important Notice

FTMSGlobal is longer taking admissions in Singapore. Please check with other regional centres: Malaysia